Robert Collier is widely regarded as one of the foundational figures of twentieth century copywriting.

He wrote advertisements (referred to as letters in his day) at a time when ad men still weren’t sure exactly how to proceed each time they sat down to write.

Collier was no different.

Of his first sales letter, written in his early twenties, he said: “I knew as little about the writing of letters as any one who ever took his typewriter in hand to tackle the job. But I was full of an idea, and it came out all over in that letter. And that is what counts.”

Along the way his intuition for what needed to be said in his letters to make the sale, tempered by the hard sales numbers from direct mailings for products that ranged “from coal to coke right on down to socks and dresses”, slowly transformed in his mind into a theory of salesmanship in print that culminated in his publication in 1931 of “The Robert Collier Letter Book” [Ref. 1].

On earlier editions of Robert Collier’s book the tagline read appropriately enough: How to Write Successful Direct Mail Letters. [image credit: amazon.com]

In it he spelled out in the opening paragraphs the six essential elements he felt were required of every good sales letter.

The real purpose of that chapter however was not to dwell on letter writing, but to offer a window into the early years of his working life, when his first inclinations to produce copy arose out of the simple need to solve an immediate business problem.

His first sales letter did not contain all of “the six essentials”, but it was nonetheless a very successful letter.

By the time you’ve finished reading this page you’ll be able to see perhaps why his letters met with an uncommon degree of success, and judge for yourself the importance of those six essentials.

More importantly, you’ll discover as I did how Collier somehow managed to intuit an approach to doing business that foreshadows by a full century the same emphasis on the importance of custom sales messaging that characterizes the recently developed ASK Method approach to formulating sales funnels.

How To Write A Great Advertisement In The Age Of Iron Works

Prior to the period 1907-1908, when his skills as a high persuasion salesman had become plain enough to those he worked with, Robert Collier was completely untested as an ad man.

Advertising wasn’t even his chosen profession.

Though it easily could have been.

His uncle was Peter Collier, a successful New York businessman and founder of a long-running popular news magazine called “Collier’s Weekly”.

Robert Collier’s own father worked as a foreign correspondent for the publication, which did enormously well up until the post World War II years when it failed to keep pace with the interests of its readers and it was forced to finally close its doors in 1957.

If he had really wanted it, Collier could probably have packed his bags, moved to New York, and leveraged the family connection to proceed directly into the world of publishing.

But Peter Collier had already gone out of his way to make clear his thoughts on the matter: he did not want his nephew to enter the business.

Not until Collier “could bring something to it they could get nowhere else”.

It later turned out that the older man would get his wish.

At any rate the publishing world was not to be in Collier’s immediate future, not the least compelling reason of which was an inner voice telling him that his calling lay elsewhere…

Everyone around him agreed that Collier’s place seemed to be with the church.

And Collier very nearly did become a clergyman, but at the last minute he thought better of the idea.

When he finally did step out into the world he decided to trek east, but not to New York where he would eventually spend many years in the advertising department of his uncle’s magazine.

Instead, when Collier first set out in search of a job it would be for work of a more tangible nature than either the church or the publishing industry was ever likely to provide.

The Journey To Copywriting Genius Takes A Dogleg – Through Coal Country

At the same time that Collier was evaluating his career options a considerable portion of the money pouring into the local economy had as its source a kind of nationwide frenzy to complete the iron infrastructure of the United States.

The ever-growing need for steel to build rail roads, locomotives, ships, buildings, bridges, even household stoves, meant that fuel to power the blast furnaces which rendered iron ore into high grade steel was continually in demand.

It was 1905, and at that time coal was considered to be “literally the power that moves the world” [Ref. 2].

It was the cheapest and most efficient energy source of the day, making it a heavily sought after commodity.

And because of this the coal mining industry was booming.

Four hundred million tons of coal were being mined annually in the U.S. and the bulk of it from a region just a few hundred miles east of Collier’s home town of St. Louis, Missouri.

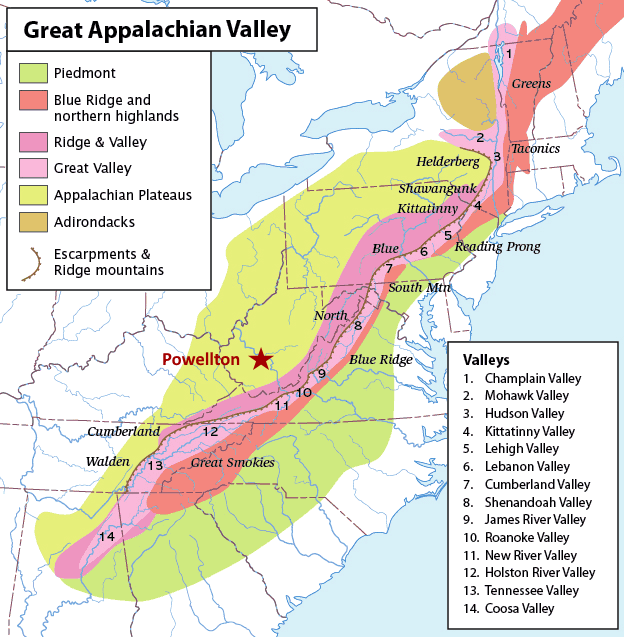

So perhaps for no other reason than he decided it made sense to go where the money and the jobs were to be found, Collier soon arrived in the small enclave of Powellton, West Virginia and secured for himself a job as a mining engineer.

But if there was ever a place in which great ad copy might be expected to bubble up in response to the needs of the moment, it was not Powellton.

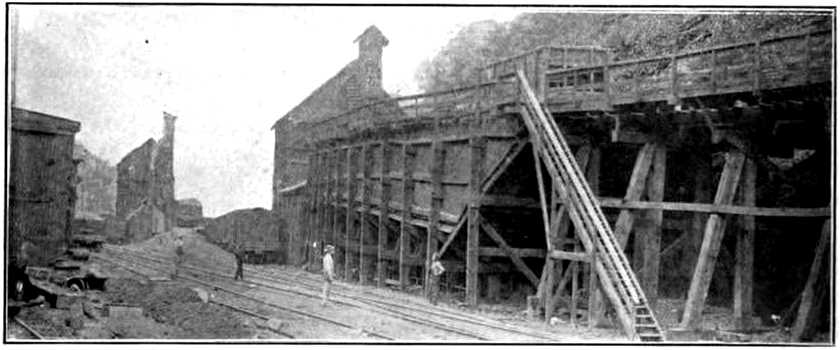

Owned and run by the Mount Carbon Company, the remote outpost was located on the upper part of the Armstrong Creek five miles from Mount Carbon.

Powellton consisted of little more than the coal-processing plants where product was prepared for shipment up or down the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway line, plus housing the mining company had put up for its 270 workers.

The only other significant architecture at the location was a collection of 202 brick ovens that were used to “cook” the dirty combustible rock they pulled from the ground into a cleaner, more desirable end product known as coke.

The Powellton coke crushing plant of the Mount Carbon Company, circa 1905. [image credit: Ref. 2]

Powellton hummed with the kind of back-breaking energy required to extract and then market a total of 150,000 tons of coal every year.

But it was a primitive environment, and compared to bustling St. Louis, the fourth largest city in the United States with a population of six hundred thousand, Powellton must have seemed to Collier strangely disconnected from the world of men.

He would have been reminded of this each time he strolled to work each morning and gazed about him at the rolling hills of West Virginia.

Slow Bake: A Recipe For Coal 300 Million Years In The Making

West Virginia, nicknamed The Mountain State, is known for its lush but rugged terrain, three quarters of which is covered in forest.

It has probably always been this way.

To it’s south, running through the border it shares with the neighboring state of Virginia, right on the doorstep of Powellton, lie the Appalachian Mountains.

And beneath the Appalachians and the terrain that surrounds them lie vast deposits of coal.

How the coal got there is a story in itself, a little of which is worth telling just to better understand what it was that Collier would be tasked to sell to coal merchants – customers of the Mount Carbon Company who until then purchased coal mainly by the ton, taking into consideration little about the properties of the individual seams.

The story of West Virginian coal involves a period 300 million years ago when what would eventually become eastern North America was covered with low-lying tropical swamp forests stupendously rich with moss, ferns, and other vegetation that thrived in the marshy environment.

Back then the mountains in Collier’s back yard were nowhere to be seen, and the lush ancient plant life would not only eventually become the substance of every coal-bearing seam discovered in the eastern United States, but also the attracting force responsible for pulling into the region each of the hundreds of thousands of coal-mining hopefuls that looked to make their fortune in the decades following the Civil War.

Coal was literally dirt cheap.

But unlike gold which had drawn miners west half a century earlier, and proved to be elusive, there was no shortage of the oily black rock that came out of the West Virginia hills.

A good mine like the one working the Powellton seam could shift a ton and a half of raw material for every miner on the payroll.

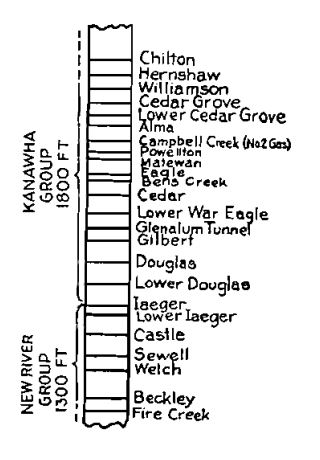

Coal miners of the day would carve out underground chambers in the hills of West Virginia and discover horizontal “bands” that alternated between thick layers of coal and dividing sheets of sandstone or shale.

A layer of shale varying between 1 and 3 inches in thickness was known to separate the upper and lower halves of the seam that Collier would later be tasked to sell:

In the Vulcan No. 1 & 2 openings what is known as the Powellton seam is being worked. This is a soft coal seam and is only found in some sections of the Kanawha coal field, and when found is located about middle ways between the No. 1 & No. 2 Gas coal seams, and varies in thickness from four to six feet, and usually has a small slate band in the center of the seam. It is an excellent coal for gas, coking and steam raising purposes. The coal is mined principally by pick miners who are paid 40 cents per short ton, run of mine.

Annual Report Coal Mines In The State Of West Virginia, U.S.A. 1904

The bands were the result of the Earth long ago undergoing alternating periods of global warming and cooling that caused the major ice sheets of the day to expand and contract.

When the ice sheets were melting the sea level would rise and sweep inland across the eastern seaboard, covering the swamp forests, burying ground-level plant life and the peat-laden marshlands below layers of silt.

Then when the sea receded as temperatures around the globe fell, and the ice thickened once again, the swamp forests recovered.

For nearly 20 million years the sea behaved like a gigantic energy pump that periodically buried under layers of silt the carbon-rich organic material that had accumulated at the bottom of the North American swamps.

And for the next 300 million years, there the buried organic matter remained, all the while subject to the slow bake of geological heat and pressure that ultimately converts plant debris into coal.

So by nothing more than a complete fluke of nature, one that involved cycling global temperature, the absence of plant-eating bacteria yet to evolve on the planet, and a complete absence of elevated terrain, more coal was laid down during that period than during any other in the history of the world.

In fact so much sedimentary material was deposited in the region that today the vertical distance by which the youngest and oldest seams are separated exceeds 3,000 feet.

The Appalachian Mountains wouldn’t appear on the scene until another 30 million years had passed and the coal-rich subterranean rock of the Earth’s crust began to pile up on itself after the two continents ancestral to Africa and North America collided with each other.

Had Collier gazed southward from the window of his office in Powellton when the Appalachians were first formed he’d have seen mountains of stone rivaling the Himalayas in size, with jagged snow-capped peaks rising to at least 20,000 feet.

Since then the peaks of the Appalachians have been eroded almost to a flat plain.

It is only the actions of more recent geological events that have partially built them back up again – though nowhere close to their original spectacle.

Collier was well-educated for his time, but about the geological history of the area it is quite possible he knew nothing.

What he would have known is that of the many grades of coal that are minded in the U.S., the only one that mattered to the Mount Carbon Company was bituminous coal.

Robert Collier Discovers That Marketing Coal Is A One-Size-Fits-All Business

Bituminous coal accounts for approximately one half of the coal mined in the U.S. each year and is representative of virtually all the coal found beneath the Appalachians.

It is not the highest grade of coal.

That distinction goes to anthracite, which besides being the rarest form of coal (making up less than one percent of total U.S. coal production) is found primarily in Northern Pennsylvania.

Anthracite is a hard, shiny gray mineral composed almost entirely of carbon.

Under the right conditions it can be burned in blast furnaces to produce temperatures capable of reducing iron ore to metallic iron.

It also contains remarkably little in the way of volatile materials, so it burns cleanly without giving off copious toxic fumes.

Bituminous coal on the other hand is a dirty, oily, black or dark brown rock more suited to use as a domestic fuel, but which was also valued at the turn of the twentieth century for its ability to generate sufficient heat for steam production, as well as gas for home heating.

What bituminous coal lacked in quality it made up for in sheer volume.

By virtue of the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway company, which had become a coal-hauling juggernaut, the Mount Carbon Company found itself a commodity supplier of bituminous coal in direct competition with every other coal mining operation located within hundreds of miles of it.

This kept the price of both coal and coke from rising much above a dollar per ton.

When Collier arrived at Powellton the company was relying on coal and coke brokers from the major towns of the region.

The brokers would secure orders from large buyers of a general grade of coal or coke and then tender to mining companies for the lowest bid.

For the Mount Carbon Company and every other coal mining operation, this represented essentially a one-size-fits-all approach to marketing.

Coal and coke customers were treated identically as faceless buyers whose bid was based on little more than the cost per ton at which Mount Carbon was willing to let go of its product.

Decades later advertising men like Rosser Reeves who penned “Reality In Advertising” [Ref. 3] in 1961 would labor on the importance of developing a unique selling proposition for the marketing of every worthwhile product.

Only in this way could such products stand out in the marketplace and earn their way based on a recognized ability to distinguish themselves from the competition.

But in the marketing of coal, this idea would have been completely novel when someone at the Mount Carbon Company finally realized they needed to do something to wean themselves off the brokerage system – and that unless they did so they were guaranteed never be paid more than the market rate, regardless of the properties of their product.

In his book Collier does not mention who came up with the idea, but it was common knowledge within the company that the Powellton seam produced “an unusually good grade of gas coal and a splendid coke” and surely there had to be purposes for which that coal or coke produced a far greater benefit to its end user than any other similar grade of coal or coke available to them.

If they could just figure out what those unique benefits were, and who could profit most from them, then the company could bypass the broker, sell direct to the customers most-suited to exploit their product, and they could charge more for the opportunity to meet that demand.

If done right it would mean an end to the era of one-size-fits-all marketing (represented by the use of a sales broker) and the beginning of a sales strategy that involved custom sales messaging developed for individual clients.

But neither the Mount Carbon Company nor Collier would get there overnight.

The Tale Of The Mining Engineer Who Traded His Hard Hat For A Typewriter

At some point it occurred to the company that if they were going to extol the virtues of their gas coal for its ability to produce so many cubic feet of gas for every pound of coal evaporated, then they needed to know just how many cubic feet they were talking about and how it compared to their competitors.

To get an answer to that question they sent several carloads of raw Powellton coal to be tested at the United States Government Testing Plant in St. Louis.

The results of that test showed that out of sixty-five carloads sampled from coal suppliers from seventeen different states, the Powellton seam produced more gas per pound of coal than any other sample tested, with one exception.

Certainly their coal was easily the best in the district for purposes of gas evaporation, and also stacked up extraordinarily well when compared at the national level.

They finally had their unique selling proposition and independent proof of the veracity of their claim.

All they needed now was to identify prospective customers for whom an appeal to the number of cubic feet of gas per pound of evaporated coal rivaled buying considerations based on nothing more than the cost per ton of coal.

Every gas company within hundreds of miles of Powellton was suddenly a prospect that might well be convinced to pay a premium of 25 to 33 percent on the company’s superior “gas coal”.

It was at this point that Robert Collier’s exposure to the world of publishing, and the business of advertising which paid for it all, must have kicked in.

He recognized immediately the boon to the company that a great sales letter would provide.

Collier said he knew nothing of the usual rules of letter writing at the time, but he was seized by the magnitude of the opportunity before him and he made it known to the officers of the company that he had an idea he was certain was worth trying.

And suddenly he was no longer a mining engineer, but an advertising man.

With Collier now attached to a typewriter the Mount Carbon Company unexpectedly found itself in the direct mail business.

Robert Collier Outlines The Six Essential Ingredients Required Of All Good Sales Copy

Many years later Collier would come up with the six essential elements he believed were required of all good sales letters:

- The opening, which gets the reader’s attention by fitting in with his train of thought and establishes a point of contact with his interests, thus exciting his curiosity and prompting him to read further.

- The description or explanation, which pictures your prospect to the reader by first outlining its important features, then filling in the necessary details.

- The motive or reason why, which creates a longing in the reader’s mind for what you are selling, or impels him to do as you want him to, by describing – not your proposition but what it will do for him – the comfort, the pleasure, the profit he will derive from it.

- The proof of guarantee, which offers to the reader proof of the truth of your statements, or establishes confidence by a money-back-if-not-satisfied guarantee.

- The snapper or penalty, which gets immediate action by holding over your reader’s head the loss in money or prestige or opportunity that will be his if he does not act at once.

- The close, which tells the reader just what to do and how to do it, and makes it easy for him to act at once.

We could examine the first of the two letters Collier wrote for the Mount Carbon Company and which are reproduced in chapter 9 of “The Robert Collier Letter Book” to see how well Collier adhered to the six essentials he later came up with.

But the first letter of the pair, which he developed specifically for gas companies, is the less interesting of the two.

In it he drew the reader’s attention to the question of just how much it was they were then paying for each cubic foot of gas generated from every pound of coal processed, regardless of its source.

In essence he was entering into the conversation going on in the mind of his prospective customer – a tactic for which Collier would later be remembered as a copywriter.

He adopted this approach because gas companies routinely discussed profitability figures in their own circles in terms of the price per 1,000 cubic feet of gas at which they were prepared to sell to the gas consumer.

Collier claimed in his letter that the Mount Carbon Company was so convinced of its gas coal’s unparalleled ability to produce gas volume that it was willing to ship a carload of regular grade coal to the prospective gas company at Mount Carbon’s own risk.

If after running their own tests the gas company did not see at least a 25 percent savings in cost based on gas volume considerations, well, then they would not be charged a cent for the shipment.

But if they DID confirm the company’s claim, then Mount Carbon would secure all the gas company’s goal requirements for the next year at a cost of $1.25 per ton.

Collier ended the letter with a confident request for permission to send the coal for testing.

“Is it a go?” he asked.

It was.

By changing the narrative on what was important to customers in the selection of a “good” coal, the Mount Carbon Company was inundated with orders from a very specific class of customers who were willing to pay top dollar for the company’s coal.

Other coal suppliers could battle it out among themselves for the right to sell coal (usually at the lowest price) for purposes of home heating, or steam generation, or any of the other means by which some benefit was extracted from raw coal.

So long as it wasn’t for the purpose of gas evaporation, on which the company now had a lock.

With the coal success behind him, Collier turned next to the matter of how to sell the company’s other main product: coke.

Fast Bake: How To Take What Mother Nature Bestows And Dramatically Improve On It

The Mount Carbon Company knew that selling coal in its natural state and letting the buyer determine how best to make use of it (the brokerage model) was no longer in its best interest.

Its newfound success with the gas companies proved that.

But the gas companies were particular in what they would and would not accept in regards to the size of coal shipped to them.

As was the case for every other coal supplier, nuggets from the Powellton seam had first to be screened for size before shipment.

Anything too small could be used instead for the production of coke, where chip size was not an issue.

Coke is the end product arrived at when bituminous coal is heated under very controlled conditions such that only enough air is introduced to allow the volatile material in the coal to combust (in the top part of the oven) and be expelled as waste gas.

As the volatile component is driven off, the coal is slowly baked from top to bottom into coke over a period of two to three days.

The result is a concentrated form of carbon (around 90 percent by weight) mixed with “ash”, which is the mineral component (mainly alumina and silica) that is left when the coke itself is burned during commercial use.

Also present in coke, because they are present in raw coal, is a minute quantity of sulphur and a touch of phosphorus.

In effect, coke can almost be thought of as an artificial form of anthracite – a high-grade clean-burning fuel that plays an essential role in the steel-making industry.

In fact, for every ton of iron or steel produced in a steel-production facility, a ton of coke is consumed in the chemical reactions that generate the intense heat of the blast furnace and which convert iron oxide into metallic iron.

The Mount Carbon Company had built 202 “beehive” ovens, the largest collection of such ovens on the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway line, so that they could cook coke and supply it to the ever-hungry steel industry, and for every ton and a half of coal they “cooked” a ton of salable coke was produced.

High quality coke, as it turned out.

How To Sell To A Market Completely Obsessed With Fire And Brimstone

By a stroke of luck, not only was the Powellton gas coal a great evaporator, it contained remarkably little in the way of the two impurities that matter most when it comes to either producing iron or working with it: sulphur and phosphorus.

When a bed of plant debris is submerged by shifting bodies of water, as happened so many times in the coal-making history of the region, the type of flooding plays a key role in how much sulphur eventually finds its way into the resulting coal deposit.

Flooding that takes place as a result of rising sea levels contributes to higher levels of sulphur as sulphates and organic sulphur from marine organisms which are laid down in the geological record end up leaching into the fossilized plant matter below them.

Fresh water floods, on the other hand, lead to lower concentrations of sulphur.

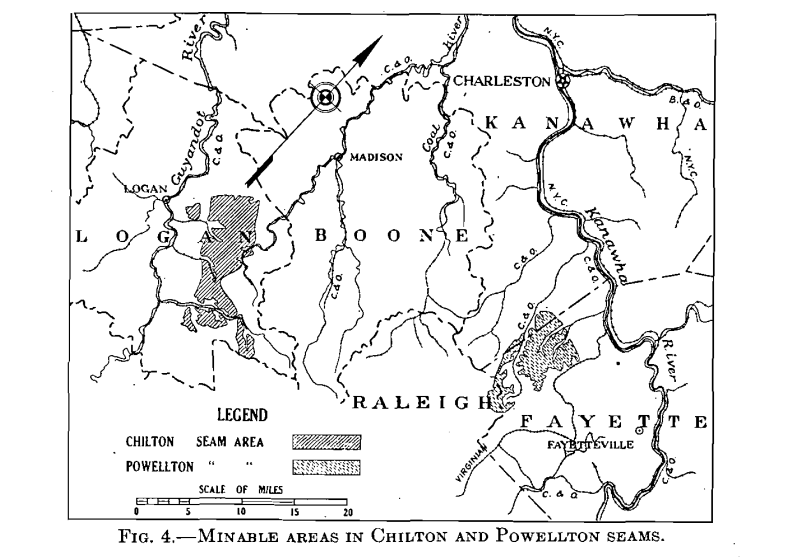

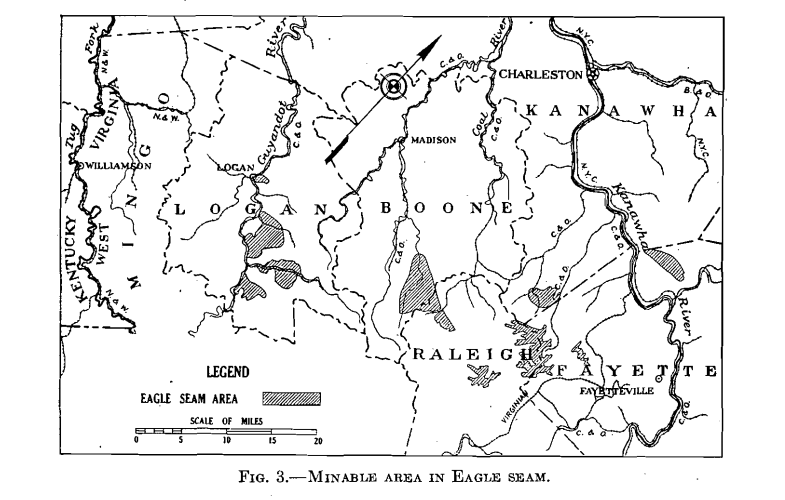

The coal seams of West Virginia stack vertically for more than 3,000 feet. [image credit: Ref. 4]

For sulphur level comparison purposes, the table below shows two other well-known deposits in the West Virginia coal fields, known as the Eagle and the No. 2 Gas seams.

Despite very similar concentrations for every other important component found in coal, the No. 2 Gas seam contains more than half as much ash and sulphur.

The Eagle seam is of particular interest.

In part because this coal sample [Ref. 5, pg. 250] is known to have been mined by the Mount Carbon Company by 1910.

The Eagle seam is also of interest because in addition to providing us with a number for the phosphorus content (not always present in coal analyses), the sample used to provide the analysis was also coked in the company’s own coke ovens (see second table shown below).

But Collier never mentioned Eagle in his book, either because that seam had not yet been located (it occurs at a depth in the ground 150 feet or so lower than the Powellton seam), or because it was considered of secondary interest to the company.

According to coal field records published in 1932 [Ref. 4] the Eagle seam was mined by the Mount Carbon Company on two relatively small tracts of land located on the outskirts of the Powellton coal field.

Coal from the Powellton seam was mined on a tract of land concentrated around the main fork in Armstrong creek, 5 miles upstream from the Kanawha River. [image credit: Ref. 4]

Compared to the 80 square miles of Powellton coal, the closest patch of Eagle seam coal coincided with Cabin Creek to the south west, and spanned an area just 6 square miles in size.

Coal from the Eagle seam was mined from patches of land scattered over a region of West Virginia that stretched more than 50 miles. [image credit: Ref. 4]

Here’s what the coal from the Powellton and No. 2 Gas seams looked like to coal buyers in 1906 (and in the case of the Eagle seam, coal buyers in 1910):

Coal Seam Analysis – Averaged Percentage

| Component | Powellton seam | Eagle seam | No. 2 Gas seam |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture | 0.98 | 0.71 | 0.76 |

| Volatile matter | 34.18 | 31.38 | 35.16 |

| Fixed carbon | 62.29 | 64.37 | 60.12 |

| Ash | 2.35 | 3.54 | 3.61 |

| Sulphur | 0.63 | 0.75 | 1.01 |

| Phosphorus | … | 0.004 | … |

It was no secret that coal from southern West Virginia was favored by the steel industry (where such characteristics of coal could not be ignored) for its low concentration of ash, sulphur, and phosphorus.

Coal industry journals were in the habit of publishing content analyses (like the one above) of the coal and coke coming out of the mines of all the major coal fields.

But according to Collier, it wasn’t until some time around 1906-1907 that the Mount Carbon Company realized the need to begin paying attention to what those numbers actually meant to their end customers.

At least, if they wanted to understand what it was that really distinguished their brand of coke from that of the competition.

How To Figure Out What Really Makes Your Customers Tick – By Asking Them Directly

The Mount Carbon Company decided to contact end users of their coke (mostly foundrymen) and simply ask them just what it was they found most appealing about the purity of the coke produced from the Powellton seam.

In essence they wanted to know what challenges their customers faced – what the obstacles were that might be overcome using the special blend of coke coming out of the ovens owned by the Mountain Carbon Company.

This mirrors the approach to marketing taken today with Ryan Levesque’s ASK Method.

Rather than contact customers individually, as Collier might have been forced to do, today we can use email marketing, or an online advertising campaign, to invite prospective or (even better) existing customers to respond to a “deep dive survey”, the purpose of which is to ask them about the biggest challenge facing them in their business.

As a result of their own survey Collier and his peers discovered that steel makers routinely struggled with an issue that depended critically on the quality of the coal they were being sold.

It was of paramount importance that steel used in the production of railway line should stand up to the tremendous stresses exerted on it by passing locomotives.

High quality railway lines were designed to withstand cracking under the strain, and this was a characteristic of the metal directly impacted by uncontrolled phosphorus contamination which acts to reduce the flexibility of steel.

Unlike sulphur, which is an external contaminant introduced over long periods of time, there is more than enough naturally-occurring phosphorus present in plant matter to account for its presence in coal.

Steel makers during Collier’s time strongly favored coke with a phosphorus concentration no greater than 0.017 to 0.020 percent [Ref. 6, pg. 68].

The Powellton seam must have satisfied this requirement because the Ashland Steel Company was easily convinced to pay 25 cents more for coke coming out of the Mount Carbon Company’s ovens than for coke sourced from anywhere else.

How good was their product?

Unfortunately, public records for the period when Collier worked at Powellton seem to be absent an analysis of the coke produced from the Powellton seam.

Analysis of a similar coke, however, is available and perhaps provides some insight to the purity of the Powellton seam.

Coke was later produced by the company from the Eagle seam, which as the table above shows was very similar in coal composition to the Powellton seam, came from the same geographic area, and from the same geological time frame (within a million years).

The Eagle coke contained just 0.0013 percent phosphorus [Ref. 5, pg. 250]:

Coke Analysis Of Eagle Seam – Percentage

| Component | Eagle seam |

|---|---|

| Moisture | 0.05 |

| Volatile matter | 0.64 |

| Fixed carbon | 91.49 |

| Ash | 7.82 |

| Sulphur | 0.72 |

| Phosphorus | 0.0013 |

This concentration of phosphorus is a factor of 10 smaller than was the limit generally deemed acceptable to the steel companies.

Even if the Powellton seam contained twice as much phosphorus as the Eagle seam it would have appealed strongly to the Ashland Steel Company.

Securing the business of Ashland Steel was a good start, but the Mount Carbon Company needed more customers and so they turned to makers of stoves and ranges who, it turned out, were just as particular about the concentration of sulphur in the coke they purchased as the steel companies were about phosphorus.

The problem the stove makers faced was that they had to remelt the iron from the steel companies before recasting it in the form of kitchen appliances.

In doing so the sulphur in the coke had the tendency to combine with the iron, and in the process of solidifying it would weaken the steel, often producing bubbles and cracks.

Additionally, sulphur makes steel brittle at high temperatures, and therefore difficult to work with a hammer.

Powellton’s low sulphur content appealed strongly to the stove and range foundries.

The only fly in the ointment was that they were located some distance from Powellton.

Far enough that the penalty represented by higher shipping costs outweighed the benefits they would have derived from purchasing the low-sulphur Powellton coke.

Competitors closer to the foundries that sold coke almost as good on the basis of sulphur contamination had an advantage that was all but impossible to beat.

If the Mount Carbon Company was going to secure stove and range business for its coke it would have to find a more compelling benefit to dangle in front of prospects than just the sulphur argument…

America’s Foremost Stove Concern Comes To The Rescue

For a while Collier and the officers of the company were stymied.

Their biggest challenge was to see if they could come up with ANY additional argument that favored the use of their coke by anyone for whom low sulphur content was already appealing, and that meant continuing to think about day-to-day operations in the stove and range business.

“We worked on that for quite some time,” said Collier, “talked to different founders to get a line on their problems, studied numerous books on the subject and finally stumbled on the answer almost by accident.”

Had they not at that time been utterly focused on finding their coke’s “killer application”, when the Mount Carbon Company finally caught a lucky break they likely would have allowed the opportunity to slip by undetected.

Here’s what happened instead.

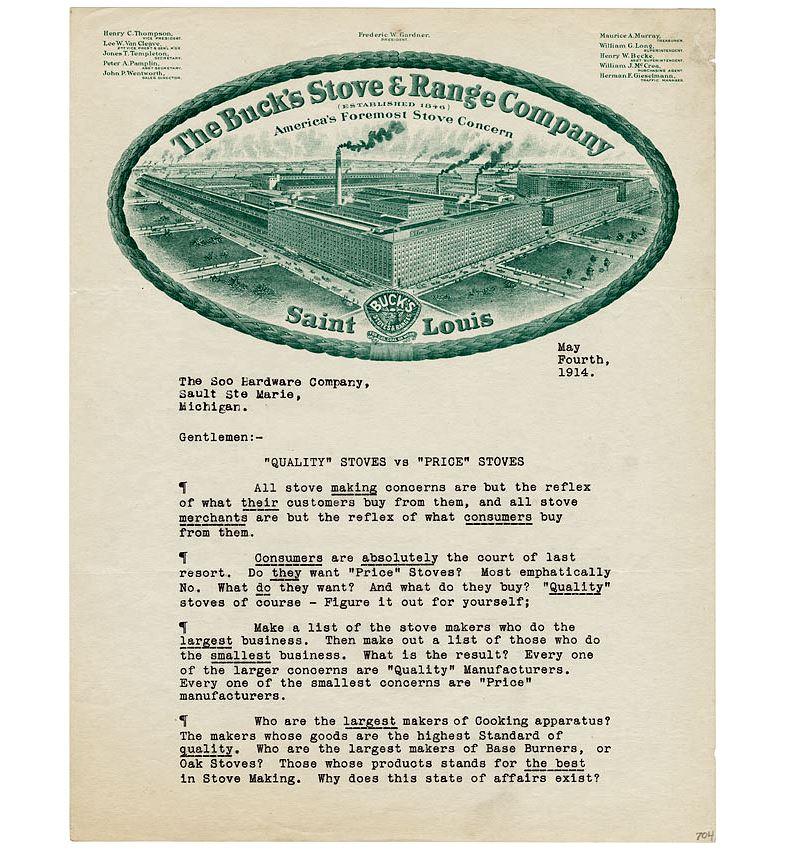

Six hundred miles away in St. Louis was the Buck’s Stove & Range Company, manufacturers of a high grade line of stoves that retailed around $100 a piece.

The stove company prided itself on its size, which it stressed was the result of strict adherence to the “highest standard of quality” in stove making.

As the letter below shows, Buck’s took pains to distinguish itself from “price” manufacturers who undercut on price and plied the market with (as the stove-making behemoth saw it) substandard offerings.

First page of a sales letter from the Buck’s Stove & Range Company (1914). Compare the style of writing in this direct mail piece (typical of the day) to Collier’s letter to foundries like the Buck’s Stove & Range Company. [image credit: Ref. 7]

For the Mount Carbon Company, one hugely important consequence of the stove company’s elitist mindset was its dedication to quality.

Buck’s was prepared to pay almost any premium to obtain the highest quality work materials for its foundry.

So when it called for samples of coke that might be able to meet the high standards the stove company set for itself, the Mount Carbon Company was not excluded on the basis of freight cost alone.

Better yet, the size of the contract up for grabs was substantial.

Out went a carload of coke to St. Louis to join the other half dozen coal companies whose claims suggested they should also be in the running for the contract.

Not willing to sit on their hands, executives at the Mount Carbon Company began to devise a plan to undercut their competitors on pricing if at the last minute it seemed that might secure them the contract.

After all, they were competing with cokes developed from some of the purest coal seams in the nation.

Nobody thought their line of Powellton coke was a shoo-in.

But before they could put anyone on a train to St. Louis they received notification that they’d won the contract, at their stated bid price.

Powellton coke had gone up against the best cokes and the best salesmen of their competitors, and still, it had won!

Child’s or salesman’s sample stove from the Buck’s Stove & Range Company of St. Louis, cast iron, circa 1900. [image credit: icollector.com]

What had the Buck’s Stove & Range Company seen in the Powellton coke that it caused it to immediately award the contract without any negotiation whatsoever?

Out went a representative of the Mount Carbon Company to St. Louis to find out.

And what they learned changed the fortunes of the coal mining company, securing for themselves, as Collier described it, “almost a monopoly of the stove and range business in our territory”.

What they discovered about their coke had nothing to do with its low sulphur content, though that was an important and valuable characteristic.

It was the coke’s high carbon and low ash content which generated enormous energy in the remelting cupolas used to recast solid iron into molten metal.

Whereas burning one ton of most other cokes melted eight or nine tons of iron, the Powellon coke melted fifteen!

Even figuring in the costs associated with coke shipment, this dramatic increase in heating power would almost cut in half the cost to the Buck’s Stove & Range Company of melting each ton of iron recast into cooking appliances.

It was a breakthrough for the Mount Carbon Company and a revelation to Collier who understood that the new language with which he could sell the company’s excess coke supply was not to be found in low sulphur and phosphorus arguments alone, but in raw heating power, the yield characterized by the number of tons of iron melted for every ton of coke consumed.

How To Write A Sales Letter That Brings Home The Bacon

If one compares the sales letter above from the Buck’s Stove & Range Company with the one found below that was written by Collier to secure foundry business on the basis of Powellton coke’s ability to melt iron it should be evident that the styles are wildly dissimilar.

Collier wraps the details of his offer in a compelling story – one that, by virtue of the fact that he is naming names, easily persuades the reader that his claims must be true.

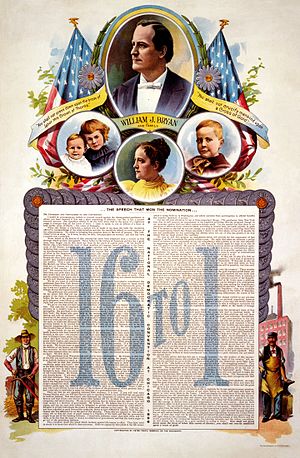

William Jennings Bryan and his 16 to 1 “free silver” presidential campaign, 1896. [image credit: wikipedia.org]

He makes it clear that to get the business of the Buck’s Stove & Range Company the coke supplied by the Mount Carbon Company had to first blitz all other competitors by performing like no other coke before it.

For the most part the letter is remarkably easy to interpret, even 100 years later.

Only the meaning of the opening sentence might benefit from a little in the way of background information.

In 1896, barely a decade before Collier wrote his letter, presidential candidate Senator William Jennings Bryan had made a run for the Oval Office on his “free silver” campaign, in which he pledged to decentralize the gold standard by introducing an equivalent silver currency, with 16 silver dollars to match in value every one of gold.

The result, said Bryan, would be a substantially stimulated American economy – but it was a claim that received wide public skepticism and Bryan never made it into office.

Collier seized upon that mildly outrageous claim, still fresh in the minds of the men who operated foundries in 1906-1907, to kick off one of his own and grab his reader’s attention…

ROBERT COLLIER’S POWELLTON COKE SALES LETTER – CIRCA 1907

When Bill Bryan first sprung his 16 to 1 ratio upon a waiting world, founders and business men generally called it visionary and impractical – said it wouldn’t work.

So when Bill Smith, Cupola Foreman for the Buck’s Stove & Range Company of St. Louis, proudly strode into the President’s office with his report of a 15 to 1 melt, he wasn’t surprised to meet with only skepticism on the part of that official.

“You’re getting your politics mixed with your melting figures!” accused the Boss. Bill may lack some of the eloquence of his namesake, but no one ever accused him of running away from a scrap. So the upshot of it was that the President agreed to be on hand at the next melt.

Sure enough, Bill’s figures proved to be right! They didn’t equal Bryan’s 16 to 1, but they averaged a good 15 tons of iron to every one of coke!

Of course, Bill modestly disclaims the credit. “Anyone could do it with that coke,” he says. “It’s got a structure that’d carry the Eiffel tower. And as for sulphur bubbles – it just never heard of such words.”

And that’s the reason Powellton Coke gets the Buck’s Stove & Range contract this year, in direct competition with and after thorough tests of every good coke on the market. That’s the reason the Gallipolis Stove Company, the Huntington Range Company and a dozen others have been using Powellton Coke for years.

Of course, some of them stray away occasionally. We’re none of us proof against the siren song of low price, but when they begin to figure the cost of the coke in tons of iron melted, as the Buck’s Stove & Range Company did; when they find that on this basis Powellton Coke is costing them only 47 cents a ton of melted iron against 80 cents to 90 cents for any other brand, and when they add to that the cost of scrap castings due to sulphur and phosphorus, they always come back, and it’s a long time before they stray again.

If you figure your coke cost, not on the delivered price of the coke, but on tons of iron melted – if you are buying high carbon heat-content, and not sulphur, ash and phosphorus – we have some figures that will interest you.

May we send them?

The Mount Carbon Company

The letter was a resounding success.

Did it contain each of the six elements he later suggested were essential to the success of all good sales letters?

No, but it came close – and more importantly, it worked.

Finally Collier was speaking the same language as the men who worked daily with the finest quality cokes and who understood the characteristics that separated those grades of coke from the competition.

For the Mount Carbon Company that understanding revolutionized their approach to securing business and taught Collier lessons that he would use repeatedly in advertising in the years to follow.

Lessons that echo the approach of the ASK Method of dialing in your sales message:

- Make it your business to find out what it is that keeps your customers up at night.

- Seek out their single biggest challenge and resolve to solve that problem for them.

- Listen to how your customers talk about their problems so that you may learn to talk that way too – be it to echo frustrations equivalent to cubic feet of gas, thermal units of steam, or tons of melted tons of iron – so that the promise of a results sells itself.

- Customize your sales message to the specific needs of the type of customer you are courting.

- Look for ways to continually improve upon your solution so that to your customers you remain the clear choice of solution.

These ideas about how to put together advertising campaigns that work are just as valid today as they were when Collier stumbled across them over 100 years ago.

Today it’s easier than ever to take advantage of these ideas and implement them in our own businesses at a pace that would have astounded the young Robert Collier.

We can tap into the mind of our market with online ad campaigns and extract vital information in a matter of days or just hours, without ever having to meet face to face with our prospects.

Then we can turn around and use those insights to formulate custom sales messages that penetrate right to the heart of our market’s deepest fears and desires.

The result is lead-generation and sales conversion rates that are often double or even triple that of the one-size-fits-all approach to campaign design.

This can easily be the difference between a campaign that flops and one that succeeds beyond all expectations.

As I write this, possibly the only marketing system that has been designed from the ground up to take advantage of these ideas is the ASK Method by Ryan Levesque.

For more information about that process, and how you can get started with it, I recommend checking out my article on How to survive building your first ASK Method sales funnel.

- The Robert Collier Letter Book. Pub 1931

- Chesapeake & Ohio Railway Company: Official Industrial Guide and Shippers’ Directory. Pub 1906

- Reality In Advertising. Rosser Reeves. Pub 1961

- AIME Technical Publications and Contributions Class F-L. Southern High-volatile Coals for Metallurgical Uses. Pub 1932

- West Virgina Geological Survey, Bulletin Two, Levels Coal Analysis. Pub 1910.

- The ABC of Iron and Steel. Pub 1919

- Bucks Stove Aand Range Company sales letter, 1914. Used under a CC BY/NC license from the Copyright Advisory Office of Columbia University.